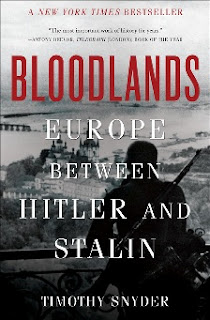

On January 26, the Marcus Orr Center for the Humanities presented the Sesquicentennial Lecture in History: Dr. Timothy Snyder, Bird White Housum Professor of History at Yale University, spoke on his prize-winning book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. It has been named a Best Book of 2010 by The Economist, New Republic, Guardian, Reason, and Forward, and it has been translated into twenty languages. "A historian of the highest caliber,” remarked Andrei Znamenski, an Associate Professor of History. “I love that the Marcus Orr Center was able to bring him. He changes our perception of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes by putting them into the context of their times. His superb book uses the bloodlands of Eastern Europe to answer broad historical questions."

Before a packed house at the University Center Theater, Dr. Snyder delivered a thorough, insightful, and provocative lecture that inspired many conversations in the lobby and beyond. "Dr. Snyder brought a fresh perspective to a number of issues that still concern us today," reflected Amber Colvin, a Ph.D. candidate in History. Robert Davis, a senior, added that “the event was very informative. He definitely went into the history of that part of the world at that time more deeply than I've heard before, while still making it understandable." Other students called it “very well spoken and argued” and “very thought provoking and smart.” Freshman student Micah Hansen said that he “was moved by the detailed accounts of individual suffering.”

During the years 1933 to 1945, there were 14,000,000 persons killed in the lands that lay between Germany and the Soviet Union. It represented the greatest scale of killings in modern Europe and does not include soldiers (if soldiers were included, the number would reach 28,000,000). Included in the 14,000,000 were 5,500,000 of the 6,000,000 Jews killed in the Holocaust.

Why, Dr Snyder asked, isn’t this common knowledge? He thinks the reason is chiefly that we tend to partition history into subjects like the Soviet Terror and the Holocaust, seeing them as separate rather than related events. Another reason is that history is usually written about nations and told from the point of view of their governments. He maintains that affairs are not determined by national issues, that national histories can only ask questions, not answer them. He rejects dialectics, maintaining that Germany and the Soviet Union were not opposites, despite their great differences, and did not cancel each other out. In many ways they strongly resembled each other.

Most of the writing about deaths during the period centers on the Germany concentration camps and the Soviet gulags. In fact, Dr. Snyder said, most Holocaust victims never saw a camp — they were shot very close to where they lived, and many of the deaths in the gulags occurred because the German invasion cut off Soviet logistics to the gulags. But the camps and the gulags left many records, while most of those killed in the bloodlands left few or no records.

Dr. Snyder does not find it helpful to invoke ideologies as the root of the killings. Ideologies change over time. Marxism was not originally concerned with killings but became so in the Soviet system. He believes that economics played a very important role. Both systems looked to the middle lands as a way of strengthening themselves, the Soviet Union seeking to modernize its economy and Germany seeking to find agricultural lands to support its population. Both wanted to get rid of Poland as simply being in the way, but they could not agree on what should happen to Ukraine.

Bloodlands divides into three segments: 1933-1938, when most of the killing was by the Soviet Union; 1939-1941, when the two nations were allied and killings were about equal between the two powers; and 1941-1945, when Germany took the lead. The early Soviet killings were directed mostly against Ukrainians, whom Stalin blamed for the failure of his policy of collectivization. The middle period was crucial, Dr. Snyder believes. The primary damage was that entire states were destroyed, and he believes that states were very important for the protection of minority rights. With states destroyed and the rule of law at an end, minorities were perilously at risk at the hands of collaborators. Dr. Snyder cited figures that indicated that minorities had a 1 in 2 chance of surviving in states that were allied with Germany. While not good, this was in startling contrast to the 1 in 20 chance where states had been destroyed. Germany turned against its former ally and went to war with the Soviet Union in 1941. The expectation was that there would be an easy victory and that the Jews could be driven eastward. But the Soviet Union did not fall, and Germany blamed the Jews for the failure of the invasion, leading to the third phase of the killings in which most were done by Germany.

Overall, Dr. Snyder emphasized, his book is not about comparisons between German and Soviet killings. Comparisons involve separation, and his book is more about interaction between the two systems.

Recognizing that it is impossible to do so completely, Dr. Snyder urged his readers to think in human terms, not of 14,000,000 killings but rather of one killing done 14,000,000 times. At the beginning of his lecture Dr. Snyder had told how three persons in the bloodlands anticipated and prepared for what seemed inevitable death in different ways. He ended his lecture by identifying each of them by name.

No comments:

Post a Comment